How Literacy Affects Secondary Students’ Success

03/23/2024

Part 2: Challenges & Solutions

This blog is the second part of an ongoing series on giving secondary students access to the science of reading. Read part one.

More than 50 years of flawed science guiding reading instruction in our K-12 schools have created challenges for secondary students that can seem insurmountable.

Why Reading Matters

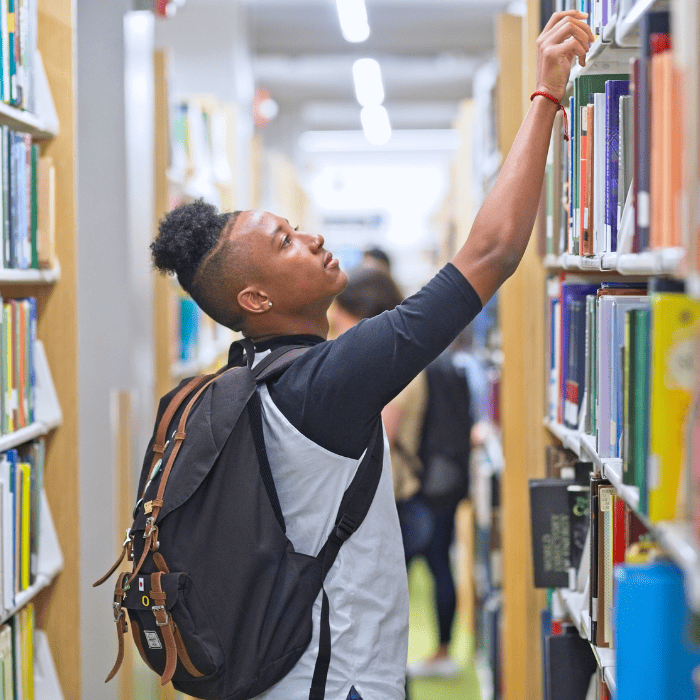

Older students are accountable for more than just reading proficiently. They must learn science, math, and history content on par with grade-level standards. To do this, they must be able to read and make meaning of complex texts independently. To ensure progress at the next grade, their knowledge base must grow significantly each year on a multitude of concepts.

Students need to know how to write for a range of purposes and audiences — research shows effective writing is impossible without a deep knowledge of the topic at hand. With the emphasis on informational, argumentative, and scientific writing (rather than personal experience) in middle and high school, students need to read a volume of texts in order to access that knowledge.

Secondary teachers must be experts in their own fields, such as biology, algebra, world history, British literature, etc., in addition to being literacy teachers. They are also tasked with preparing students to take high-stakes standardized exams with very specific requirements in the core content areas.

I’ve never met a teacher who felt they had enough time to thoroughly cover their own coursework in a school year, much less make time for additional reading interventions.

What Secondary Teachers Need to Know and Be Able to Do

As someone who taught “remedial reading” classes at middle and high school, I fought to affirm students’ brilliance and remove the stigma associated with these courses.

Older students who feel like they “can’t read” after many years of trying — and multiple years of intervention — carry a heavy emotional toll. Disillusioned students who are no longer hopeful about their own ability to read after years of harmful practices and damaging messages (even from well-meaning educators) can feel unmotivated to keep at what feels like a pointless venture. Meanwhile, the Tier 3 support these students require often eliminates the elective courses, like music or art, that bring them joy in school.

There is a scarcity of materials appropriate for students in the upper grades who require support in word recognition. Almost all materials that teach students basic print concepts feature stories about being on the playground, learning colors and numbers, and are animated with childlike images.

Additionally, I’ve yet to find a literacy conference that focuses specifically on the science of reading for older students, though events for elementary school educators are growing in number. Nearly all of the leading experts in secondary literacy focus solely on the Language Comprehension strand of Scarborough’s Rope, with the assumption that their audiences have students who have mastered the foundational skills of reading.

While traction is gaining on the power of the science of reading for multilingual learners and students with dyslexia, there is a lack of awareness on the basic components of the science of reading for school and district leaders, who should be endorsing it as a Tier 1 instructional approach for all struggling readers. Principals or central office staff may be reluctant to see themselves as instructional leaders; when the decision-makers in a school system have large blind spots around science-based instructional approaches, everyone suffers.

Facing the Uphill Climb with Hope

While the COVID pandemic impacted our national reading scores, literacy proficiency is a problem that has existed for the entirety of our lifetimes.

So, is there a reason for hope?

Yes.

We can build and expand on the progress self-educated classroom teachers are making with the students so many others have failed to reach. In some Michigan schools, middle and secondary teachers are throwing out the book on what they were taught and trained to do. They’re figuring out what works on a trial-and-error basis, succeeding—and sometimes failing—right along with their students.

What they’re learning in the process benefits all of us doing the work. In a small, unofficial case study, the teachers of that linguistics course last school year in southeast Michigan reported at the Michigan Reading Association Conference that their students gained an average of three grade levels in reading in seven months, with improved grades in their content area classes, as well.

Rather than feeling embarrassed about having to learn syllabication, word parts, and letter/sound combinations, students reported relief that their teachers were finally doing something that worked. They remained engaged, one student commenting, ‘Why didn’t anyone teach me like this before?’ With some tweaks, the teachers have relaunched the linguistics course in additional periods with more students.

Some promising solutions are happening in secondary classrooms (mostly under the radar)! They include the following.

For system and school leaders:

- Embedding literacy interventions into core content classes when possible. If pull-outs are required, use them to reinforce the specific concepts and vocabulary students are learning in their science, math, history, and English/language Aarts courses. Instead of pulling kids out to practice skills and texts from a separate and unconnected “reading program,” allow them to go back to the grade-level texts they are reading in their American Lit or Earth Science class to re-read and process, practice fluency, reinforce key ideas and complete assignments from those classes. Take time to reteach the key concepts and how to decode words with similar roots and meanings.

- Training that includes all roles within a system. Create a coherent focus that involves the district leaders who make strategic decisions, to the principals who will observe and evaluate instruction, to the teachers, as well as the literacy coaches and interventionists who need ongoing learning opportunities and regular coaching. Bonus if you can include families in the learning!

- Compensating teachers for the new knowledge and skills they will need to attain and providing the time and materials they need. In many cases, teachers for grade 6-12 students will need to adapt or create the materials that will be appropriate for older students after they complete training intended for lower-grade students.

For classroom teachers:

- Starting BIG (not small). Introduce a linguistics course with a word like pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis and show students how breaking it apart into morphemes and syllables unlocks meaning (a lung disease caused by inhaling fine particles of silica dust). Do this before students get into the one- and two-syllable words. (Yes, this is technically a “made-up” word, and it’s an excellent demonstration of how long words can consist of decodable word parts!)

- Offering the science of reading to all of the emerging readers. Phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary practice, and comprehension anchored in disciplinary content works as well for struggling readers who never got a foundation in reading as for students with dyslexia and multilingual learners. (Students who speak other languages sometimes learn faster based on the morphemes and cognates from their first language.)

- Teaching students the brain science behind how we learn to read. Unravel the beliefs within yourself and your students that reading is natural, an indication of intelligence, or can be taught through the love of books. Show them the cognitive connections with resources like How We Read, a graphic novel that explores the science of reading in an engaging and accessible way.

- Connecting skills to knowledge. If you’re teaching syllables, don’t rely on words like “cat and “dog,” which most older students may have memorized. Teach it with SAT words like “annul” (an/nul) and content words from Science and History like “mass” and “monarch” (mon/arch”). Same for teaching morphemes (the smallest unit of meaning within a word – often a prefix, root word or suffix).

What might all this look like in real-time? Leading Educators is supporting school systems with many of these aspects right now.

Check out the final installment of “Bringing The Science Of Reading To Life In Secondary Literacy Professional Learning” to find out how!