Supercharge Your Professional Learning Strategy

09/22/2022

A Recap of Rivet Education’s Professional Learning Power Hour

It’s no secret that the pandemic disrupted student learning, and many school system leaders are grappling with how to rebound. But one of the most promising solutions is getting little attention: curriculum-based professional learning.

Recently, four members of our team joined Jennifer Wells from Rivet Education for a “professional learning power hour” to delve into curriculum-based professional learning as a sustainable improvement strategy and share how we are using it to help educators in Chicago and Charleston get real results for students.

- LeAnita Garner is the Director of Content and Coaching at Leading Educators for Chicago partnerships.

- Michael Freeland is the Senior Director of Programming at Leading Educators for Charleston County School District’s Acceleration Schools initiative.

- Dr. LaKimbre Brown is the Chief of Networks at Leading Educators, where she oversees a portfolio of customized partnerships in more than a dozen cities.

- Laura Meili is the Chief Impact Officer at Leading Educators, where she heads evaluation, innovation, and program strategy.

Here, we offer a recap of what they discussed so you can make similar strides in your community.

What is Curriculum-Based Professional Learning?

Rivet Education was founded to ensure that educators receive the best resources and support available so they can teach all learners to great heights. Teachers enter the profession with tremendous passion and a desire to help students reach their goals. But few start with the instructional skills and content knowledge to craft grade-appropriate lessons and differentiate. Recognizing that fixing this gap is complex, Rivet defines high-quality professional learning and creates tools and services that help state and local education agencies put that definition into practice.

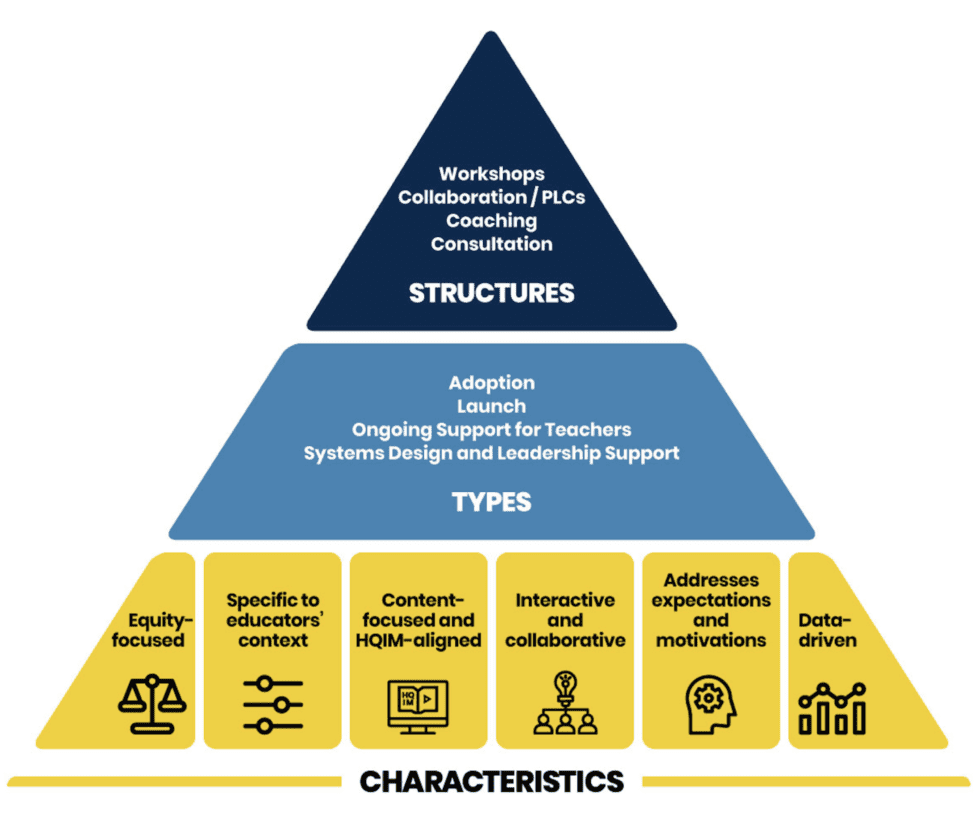

Rivet’s framework for high-quality professional learning (to the right) names the characteristics, structures, and types of professional learning that help teachers internalize and practice using high-quality curricula. Hence, students are more likely to access grade-level knowledge and build confidence in their abilities. Their related Professional Learning Partner Guide offers a searchable database of national and local professional learning providers like Leading Educators that meet the criteria.

How Does High-Quality Professional Learning Work?

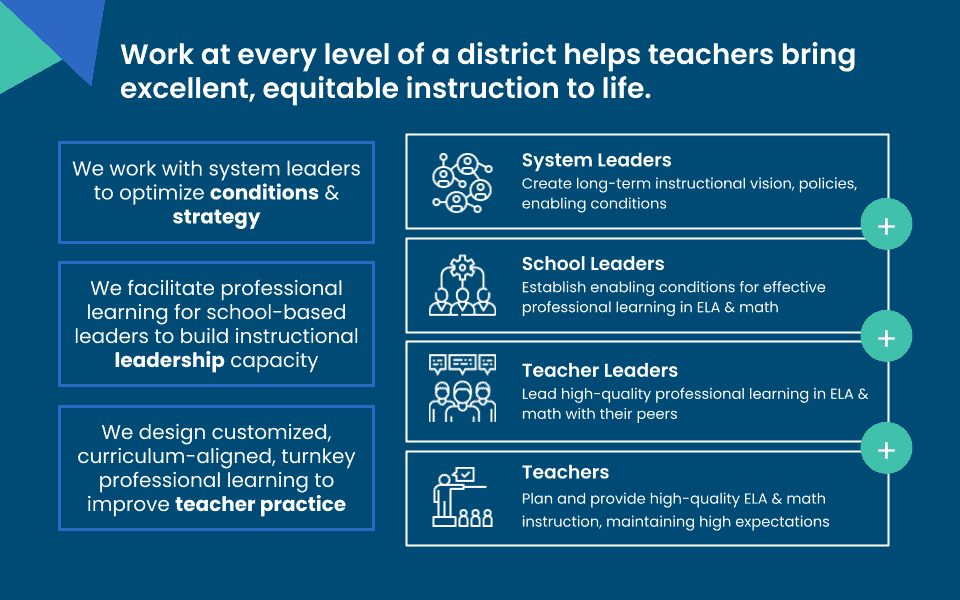

Leading Educators’ approach to curriculum-based professional learning creates cohesion between school and district leaders’ work and the collaboration teachers and teacher leaders engage in at school sites.

LaKimbre explained:

“We support districts to build the leadership, professional learning systems, and necessary conditions. When we talk about conditions, we’re speaking about things like time allocation. Do teachers have enough time to come together consistently and collaborate? Are there limited priorities so that they can be focused? And are there clear roles and responsibilities about who is doing and owning what?”

All of Leading Educators’ support aligns with the curriculum the teachers are using that day so that each session immediately applies to what they need to do in the classroom. Laura shared that four rigorous studies over the last decade show statistically significant student gains after using versions of this approach.

A new randomized control trial and implementation evaluation by the RAND Corporation of the Chicago Teacher Collaborative professional development program found significant results for students and evidence of strong implementation. This evaluation builds on what was learned from previous studies because the program specifically focused on the conditions that allow professional learning to happen with regularity and transfer into how teachers teach.

Building Teacher Leadership and Professional Learning Structures in Chicago

The Leading Educators team highlighted a few critical aspects of how the Chicago program operated and what we can conclude from the evaluation.

LeAnita started with a lay of the land. She named that teachers’ practice improves with access to the right support, such as high-quality professional development, coaching, and collaboration opportunities. The Chicago Collaborative and related RAND evaluation allowed our team in Chicago to help school leaders establish the conditions to distribute leadership and to provide opportunities for professional development and coaching for their teachers. We also supported teacher leaders to deepen their content and pedagogical content knowledge and build the leadership skills to facilitate learning to their peers.

Five research-based design features were central to our work in Chicago.

- The program’s objective was to improve teachers’ pedagogical knowledge in math and ELA with content-focused training aligned to teaching standards.

- School leaders and teacher-leaders participated in intensive training sustained over time.

- Teacher-leaders led content cycles for mentee teachers, which provided coaching and peer collaboration opportunities.

- Content cycles allowed teachers to assume ownership over their professional learning.

- Content cycles were embedded in mentee teachers’ regular work hours and extended the reach of the professional learning activities.

LeAnita described how the partnership took shape:

- 2017 was year zero. Initial programming focused on supporting district and school leaders to develop their content and pedagogical content knowledge, knowing that the ultimate goal was to focus on teacher leadership. Coaching focused on helping school leaders identify who teacher leaders could be. We also supported them in adjusting their conditions and creating the structures for teachers to lead professional development for their peers, plan for it, and collaborate with other teacher leaders.

- 2018 started with induction, where we introduced programming and coaching to our future teacher leaders to build excitement and investment in the work for all leaders. We offered opportunities such as Leading Educators Institute (which brought cohorts of teacher leader teams from four cities together for a week of learning), Regional Institute, and other workshops where teacher leaders could continue to build content knowledge.

- In the second year of programming, we developed teacher leaders’ ability to shift practice in their classrooms and among their peers by facilitating “content cycles.”

- Finally, 2020 was the most interesting year of them all. The pandemic forced us to shorten programming. But we still aimed to build a sustainable model for the teams we supported.

- We worked with school teams to observe evidence of standards-based instruction. We used an observational rubric and took the trends we saw in walkthroughs to inform continued professional development and coaching. Before the close of that scope of work, we were able to begin some visioning work with school and district leaders about the next steps beyond the partnership. We encouraged them to think about how to keep the learning and collaboration structures in place so teachers could continue growing together.

The emphasis on establishing and maintaining the conditions for distributed leadership and professional learning for teachers allowed district and school leaders to focus on improving teacher practice over time.

The Results

|

The team shared a few key learnings from the partnership. LaKimbre noted that there was a recognition that we needed to maintain a high bar for impact as professional learning providers—satisfaction data is not enough. Providers and districts need ways to monitor what is changing in classrooms. What are teachers doing today that they weren’t doing yesterday? What’s happening for students today that wasn’t happening a week ago?

She also shared that we recognized how teachers’ beliefs must shift alongside using materials and their practices. Effective professional learning starts with teachers believing that all students are capable of reaching a high bar and demonstrating their brilliance in different ways.

Using Professional Learning to Accelerate Student Outcomes in Charleston

Districts and school systems are unique, so we are taking a different approach to a newer partnership with Charleston County School District. Michael Freeland, who leads the project as Senior Director, shared what makes the features of our work with Charleston’s Acceleration Schools different. The Acceleration Schools initiative uniquely focuses on investing resources for instructional improvement in a subset of schools where students have historically experienced lower access to excellent teaching and grade-appropriate lessons.

Charleston tried curriculum adoption before, but previous PD opportunities and professional learning communities at the school level haven’t gone as well as they hoped. So, they wanted to think through how to create a more coherent and cohesive support system for teachers. This partnership focuses on talent management and adopting high-quality math and ELA materials.

Including Teachers in the Process

To ground these efforts, we spent a lot of time reflecting on Leading Educators’ system and school conditions. Early in the partnership, we did a significant amount of discovery work, where we met with teachers, principals, and district staff to identify current barriers to teacher buy-in. Like many teachers across the country, we heard teachers say they just need more planning time. But we also heard them say they wanted more time for relevant development.

Michael said,

I can remember when I was a math teacher. Sometimes we would have a faculty meeting on Wednesday, and on Thursday, administrators came around with the clipboard to see how we were implementing these new strategies. Teachers stressed that as they take on this new learning, how do they have time to practice, reflect, go deeper, and develop as educators? And so that was one place we wanted to stamp: we were designing the system along with CCSD to make sure it was meeting teacher needs.”

Maximizing Capacity with Narrow Priorities

Sometimes, there’s a disconnect between the district level and the school level, where one school is pushing specific initiatives, and then district leaders come to observe classrooms with a different checklist. In the Charleston partnership, we wanted to ensure the necessary parties were talking to each other regularly and moving in that same direction. That took a lot of change.

Charleston had PLC structures in schools, but schools used them differently, like meeting about field trips. We had to get intentional about what would happen in weekly development for math and ELA teachers. CCSD also added protected planning time in the master schedule. District leaders also allocated resources for coaching. Instead of having one instructional coach across maybe 30 teachers, they hired one ELA coach and one math coach to drive individual development at the school level.

Previously, the district offered PD over the summer, but teachers wanted it throughout the year. So, the district created time in their academic calendar for quarterly PD days. Because we launched in COVID, finding substitutes wasn’t possible. Having PD days built into the schedule has helped teachers get the time they need to develop even amid unprecedented disruption.

The Model

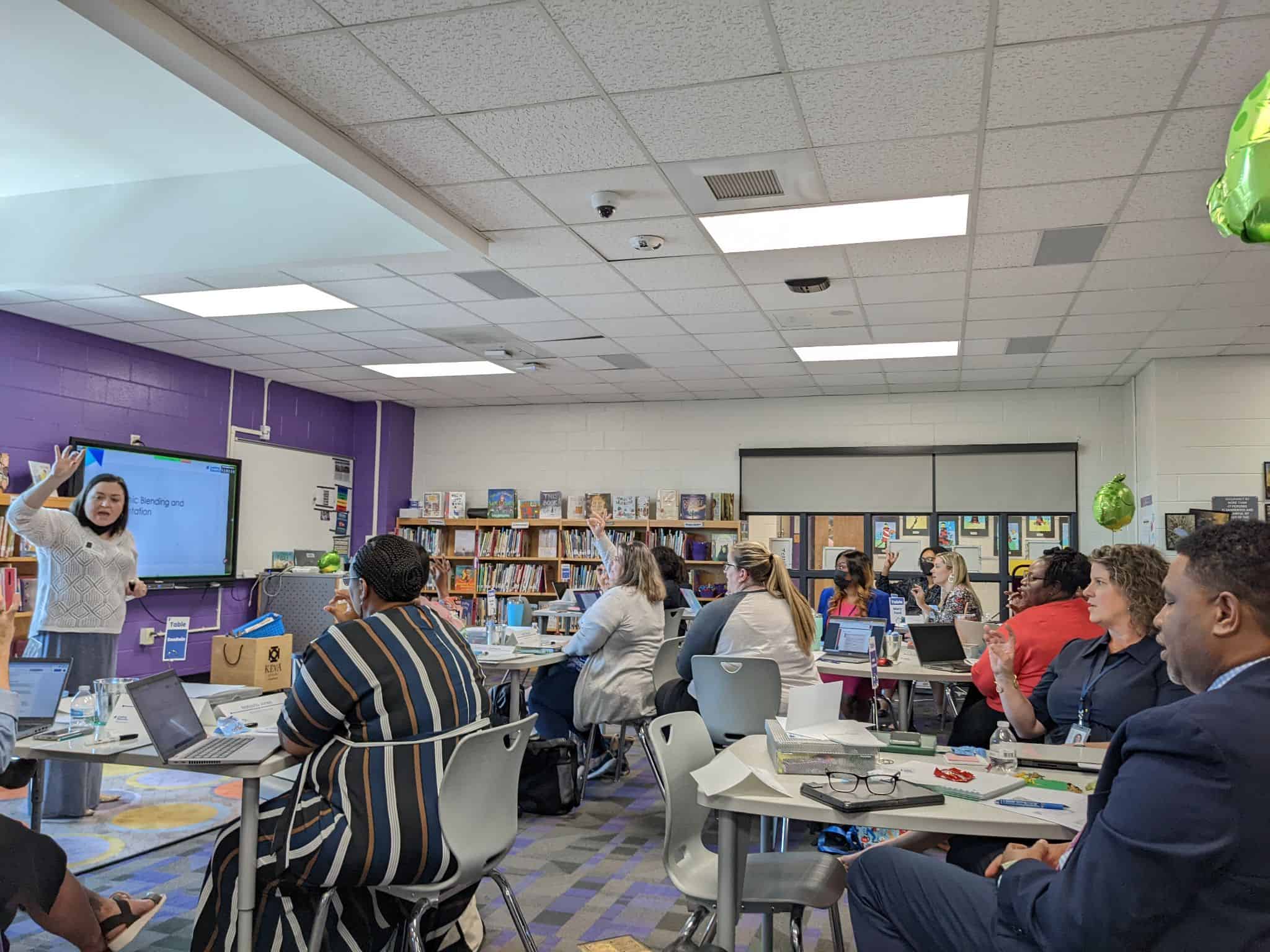

Recently, all math and ELA Acceleration Schools teachers attended their first quarterly PD workshop alongside coaches and administrators. Following that shared learning on math and ELA content, there were differentiated sessions for PLC leaders, coaches, and school leaders. Coaches, school leaders, principals, and assistant principals all support teachers’ development, so they must speak the same language and use the same indicators for success.

Sometimes an administrator might get a checklist of 50 things to look for in a classroom, but we help them narrow that focus to about two things so they can think about themselves as a coach. Michael shares, “I think that has been a big driver in some of the changes we’ve been seeing with teachers.”

After a quarterly workshop, teaching teams spend nine weeks going through cycles of planning and practice and looking at student data. They reflect on how they practice new content, deliver it in their lessons, and look at the results. These content-focused PLC blocks happen weekly, and teachers also get monthly coaching. The Leading Educators team works with the district to observe lessons during learning walks and look at the data.

So far, that data is inspiring. The most recent state assessments showed significant math and ELA growth for all Acceleration Schools students from pre-pandemic levels.

What Next? How Districts Can Act Upon These Lessons

The team shared several ways district leaders can replicate what has worked in Chicago and Charleston, especially as they made critical decisions about using pandemic relief and recovery funds.

- According to LaKimbre, a former district leader herself, it’s important to remember “that impact takes time.” Though the Charleston project started during the height of the pandemic, it was always designed to be a multi-year investment. To shift all of those systems—taking PD from being optional and in the summer to quarterly—takes a lot of changes at once. Having conversations with senior leaders early on about the time horizon helped them make some of those moves.

- Additionally, coherence matters. Teachers in Charleston and Chicago received a new set of wraparound services that don’t feel like a disparate initiative. Anyone who supports a teacher’s development is on the same page about what they are working toward.

Quick Hits from the Q&A (Edited for Brevity)

What does your discovery process look like as you’re undertaking work like this with leaders and helping them to support teachers?

Michael: A big piece is ensuring we have voice and input from people at all levels. When working with school districts, someone at the district office may give a completely different answer from somebody at the school level.

We have focus groups and interviews to ensure we build off the existing strengths. We want to see what is working, which requires us to talk to the people closest to the work and get a full picture from all the different stakeholders.

Did the shift to more PD planning and PLC time involve decreased student classroom time? How did you ensure students could stay in the classroom?

Michael: We did a lot of work on the master schedule to ensure we didn’t lose instructional time. The district also added some additional time after school. Teachers have a paid 60-minute period after school to focus during protected time.

What role has job-embedded support played in some of the successes?

LeAnita: I think what’s nice about job-embedded support is that it’s on the ground, it’s real life, and it’s an opportunity for teachers to problem solve together while they’re in the learning. Having professional learning be job-embedded allows teachers to bring the current thing that’s happening to the forefront, do some learning from collaborative planning around it, and then try it out and get feedback quickly. If you don’t have that, or when learning is far removed from the day-to-day experience, it takes away from a teacher’s ability to enact the changes you would hope to see.

Did the Leading Educators team become experts in the high-quality instructional materials the districts were adopting?

Michael: We kind of had two different routes. Charlson had already adopted a new high-quality math curriculum with which we had some experience, but we weren’t necessarily experts in it. Our focus wasn’t just on training on the curriculum but on how they could go deeper in math practice. Our team had a deep understanding of the math shifts and how those should show up in high-quality curricula. From the ELA side, we did the district’s entire training from start to finish on the EL curriculum because we had a lot of expertise with it on our team. Some of our team members have even written some of the curricula and supported that rollout.

How do you figure out that balance between job-embedded support, workshops, and what that structure of PL looks like?

LeAnita: We created an entire scope of work for the Chicago Collaborative. We knew the duration of the study, and we knew the duration of the project. And so we could map out where those touchpoints would be and what would happen during each of them. Thinking about wanting to intentionally support district leaders, wanting to support school leaders intentionally, and then focusing on teacher leaders, we had to determine which type of support would make the most sense.

It made the most sense for the school leaders to come together as a PLC, whereas for the teacher leaders, it made the most sense to go to them and be a part of their teacher team meetings or PLC after school. Striking a balance involves thinking about the long-term goals and which format would make the most sense for the goals you’ve created.

Michael: We try to be very responsive to the needs of a client or a district. And so, even in Charleston, we focus on continuous improvement and get feedback throughout the process. When we initially launched, we were focused more on the job-embedded supports and less on the workshops, but teachers needed more direct support. We shifted to doing more direct PD, bringing all the math teachers and all the ELA teachers together for those workshops—consistently reflecting and seeing where we can improve on what the district needs drives our decisions about the model we use.

Tell me a little bit about your customization. You mentioned your scope of work piece, which I think is exciting. What would you like to see places you’ve worked with continue to do as they support their teachers and students with HQIM?

Michael: I think the big thing would be continuing the work. We always want to work ourselves out of a job. We don’t want to be on someone’s budget for 15 years. So we want to ensure we’re doing our part to build capacity at the district and school levels, so they continue to strengthen. It’s always powerful when we can go back to some of our partners, whether five or ten years down the road, and still see some of those same components in place. We want to see that they’re still growing teachers and providing those leadership opportunities so that the success for students continues. That’s the big thing—making sure that the work continues—and avoiding the kind of resets that can happen with districts every couple of years.

LeAnita: For Chicago, we have really big districts, and there are lots of schools, lots of networks. It’s been a little bit of a challenge thinking about high-quality resources because schools have different things. And so one thing coming out of Chicago now is getting everybody within the same high-quality resource so that professional learning can be targeted. I think that’s something that I hope the district continues investing time and energy in.

How have these experiences affected their PL processes and practices? Did any of the ongoing work result in changes to their PL practices? And if so, what, why, and how?

LaKimbre: The partnership with Charleston started during the pandemic, so it allowed us to try out some things virtually that we had only ever offered in person and test which PL practices could be transferable and, in some cases, just as effective.

Michael: Launching in the middle of a pandemic presents a whole different level of challenges. But I would say thinking about how we leverage virtual opportunities has been a big thing. Even just offering flexibility for teachers, whether in a one-on-one coaching session or providing more opportunities for teachers to be at PD while they may need to be at home or another location. The switch to designing virtual professional development forced us to learn lessons about how we build culture and that kind of community in an online space. The other lesson has been thinking more about all the responsibilities that schools and teachers have on their plates. Sometimes in this field, you can be very focused on your priorities as a consultant, but making sure that we always know everything the district has on its plates and how its priorities might need to change is important. At the end of the day, that impacts teachers the most.

LeAnita: I think what I’d add to changes or shifts in professional learning practices would be just putting a little bit more structure and support behind teacher leadership or distributed leadership. I think that’s buzzing within the CPS district right now. I would love to believe that it’s a result of our work, but I’m sure it has to do with many other factors.

If I’m a leader, and I’m hearing this and thinking, “Oh, I would like to do something similar in my school or district,” what would be your advice to me?

LaKimbre: As a school leader or leader of schools, I would start with my master schedule and ensure that my teachers have time to come together. And then I would probably call my coaches or Assistant Principals, whoever’s leading the content or who are charged with the coaching, and audit what those current spaces are looking like, what we’re discussing. Is it focused on the curriculum? Is it? Are we talking about student progress? Are we looking at student work? Even if you don’t have a support provider, you can audit your own systems right now to make small adjustments.

Michael: I would also add opportunities to get diverse perspectives at the table. In our discovery work, there are a lot of things that the district had one perspective on, but it played out in schools differently. Getting the perspective of teachers, coaches, and principals as you’re thinking about new initiatives is essential because it also helps with the buy-in. Teachers had different energy because they felt like they were a part of the process and were co-creating some of this.

Laura: Once you get a sense of the current state and where you’re headed, I think just going back to that point about impact and understanding what success looks like and how we can learn about it is key. It’s the shift from “we did it,” and we kind of check the box of PD happening or coaches are in place to understanding the impact of the work we’re doing in workshops, school-based PLCs, and coaching. How is that shifting teachers’ beliefs, teachers’ knowledge, and most importantly, their practice and student outcomes?

Want to Take Action? Start Here.

- Get in touch with the Leading Educators Partnerships team about opportunities for customized support.

- Explore the RAND study in greater detail.

- Check out the Professional Learning Partner Guide and the Rivet Education website to assess your own professional learning strategy.